SLP-S-10,11,15 Mule Hill

While the exact location of Mule Hill was not even established until 1970, beyond that, not much was truly known concerning the siege itself. All that was really known was that General Kearny and his Dragoons had been attacked while on their way to San Diego. They took high ground at Mule Hill where they formed a defensive position on the evening of December 7th and remained there until reinforcements arrived on the early morning of December 11th, 1846.

What became apparent to the SLP is that while all previous historians of Mule Hill had focused on the south and southwest ends of the hill concerning the battle, the first-hand participants involved in the taking of the hill were giving much more attention to the west and northwest ends. The question was why?

Many historians of this battle saw Emory’s sketch map of Mule Hill as showing the two, rock outcroppings that surrounded an enclave, being the same two prominent rocky outcroppings that are visible today facing south. This, however, was found to be yet another misinterpretation of Emory’s map by historians.

This discovery was made quite accidentally when the SLP took a helicopter and photographed Mule Hill directly from above. From above, the hill looked exactly as Emory had drawn it except the two rock-croppings facing southwest were not the two croppings that Emory was denoting in his sketch.

Rather, it was the west side of the hill itself. The enclave was caused over time by natural water erosion. This gave us a new direction to look at in relationship to Emory showing where and how the soldiers entered Mule Hill upon being initially attacked. It was an entirely new interpretation of his map.

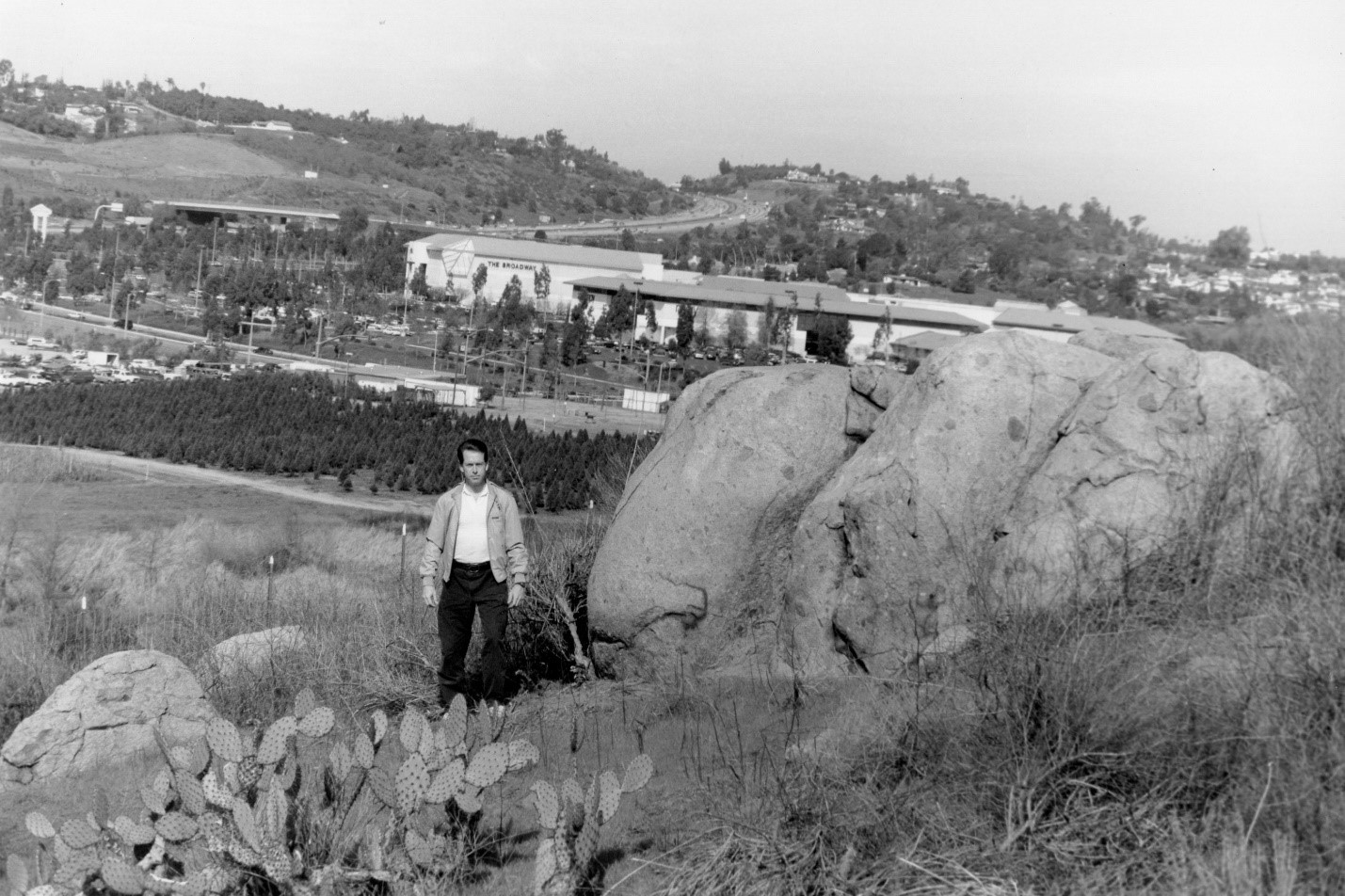

The SLP then made two very interesting discoveries. The first was photograph 85:15705 in the San Diego Archives, simply labeled “Starvation Hill.” It was mis-dated 1876.

Just a few weeks from his 21st birthday, a young Scottish immigrant named Philip Crosthwaite found himself fighting in the Battle at San Pasqual and Mule Hill in December of 1846. Crosthwaite was one of the volunteers in Captain Gillespie’s group that had met up with General Kearny and the Dragoons prior to the battle.

As soon as the war was won with Mexico, Crosthwaite remained and settled in the area. He lived for some time in Poway (not far from San Pasqual) and later even became the Sheriff of San Diego before finally retiring down in Baja, Mexico in the town that is today called Rosarita Beach.

By 1897, the Battle of San Pasqual was fading into obscurity and San Diego began to take a renewed interest in this historical battle that had occurred in its county just 50 years earlier. Philip Crosthwaite, who was then seventy-two years old, was asked to lead a tour from San Diego to the San Pasqual Battlefield, to show interested San Diegans where the battle had occurred at and to recount the events that had unfolded there. Accompanying the wagons, buggies, and horses carrying people to this event on July 17, 1897, was San Diego photographer Samuel Schiller.

The following newspaper article appeared in reference to this event:

“Battle of San Pasqual

Don Felipe Crosthwaite returned from Ensenada last Wednesday. He will go to Escondido today and tomorrow to San Pasqual, where he will meet a committee of Native Sons, and locate the battle site, where General Andres Pico whipped General Kearny December 6, 1846, and the American forces met with a loss of 22 killed.

The committee consists of L. A. Blockman, Samuel Schiller and C. E. Overshiner.

The Native Sons have started a fund, and later will erect a stone monument on the site. Don Felipe Crosthwaite participated in the battle.”

San Diego Progress San Diego, South California July 17, 1897

Schiller, the photographer, was named an actual committee member involved in locating this battle site. There is no doubt he took photographs during these two days of sites relevant to this event. This especially when present, was as an actual participant and first-hand witness to it, who showed and, explained details and locations to them all while there.

At least two photographs taken by Schiller that weekend were retained by the then “Pioneer Society of San Diego County”. These two photographs were then later turned over to the San Diego Historical Society and sat buried in the archives for the rest of the 20th century until discovered and researched by the SLP in 1996. One of these photographs was of Philip Crosthwaite standing next to some rocks atop Mule Hill.

This is what Thomas Adema, Photo Archivist with the San Diego Historical Society wrote about these two photographs:

“ Concerning photographs 85:15705 (Starvation Hill) and 85:15706 (Battlefield of San Pasqual); I believe the two photographs were most likely taken on the same day. The writing on the back of the photos are the same, as is the mounting board and size of the image. I believe the date to be around July 18, 1897. I base this date on information I found in the biographical files at the San Diego Historical Society Research Archives under Samuel Schiller. I recognize Philip Crosthwaite in the photo 85:15705 and he appears to be an age that would agree with 1897. Crosthwaite was born December 27, 1825 and would have been 72 years-old. I have enclosed a copy of the Samuel Schiller note. The Pioneer Society of San Diego County gave the photographs to the San Diego Historical Society. ”

Thomas Adema

Photo Archivist

San Diego Historical Society

The photograph of Crosthwaite standing next to the two boulders atop Mule Hill became of particular interest to the SLP. The two immediate questions raised were ‘Where on Mule Hill were these two boulders located?’ and ‘Why did Crosthwaite have his picture taken next to them?’ In other words, what was the significance of this location that Crosthwaite was trying to show us or was it just random? The background was revealing that the boulders were located somewhere on the west side of the hill. Just as Emory’s topographical map had focused on the complete west face of Mule Hill; why was Crosthwaite also showing us something from the west face of the hill?

It took several hours of searching one day before the same exact two boulders could be located. The boulders had become completely hidden under vegetation and vine growth. Finally, all cut away, the exact location of the boulders were revealed. It was located on the northwest corner of Mule Hill. Almost completely opposite from the southwest end where all previous attention since 1970, had been placed.

Both Lt. Emory and Philip Crosthwaite had given tremendous focus at Mule Hill, not facing southwest between the two croppings but rather facing directly west itself. This despite the Sorensen-Schreier dig in 1970 had found all their artifacts from between the two, large rock croppings facing southwest. So, the question was why? Why was the western part of the hill so important to Emory and Crosthwaite instead of south towards San Diego?

* * *

From 1993 to 1995, the SLP began the most intensive research ever conducted into Mule Hill. It returned back to Mule Hill with a clearer understanding of actual movements and actions by the participants in their own words. This, coupled with artifacts and their precise locations upon being found, the SLP began to paint for the first time a much clearer picture of what caused “Mule Hill” to happen in the first place. Not only how only how the military engagement transpired, but where.

On the morning of December 7th, 1846, General Kearny and approximately 149 men of combined Companies “C” and “K,” started out from the San Pasqual Battlefield to an adobe structure built simply referred to as the Snook Adobe. Fearful of being reattacked by the fierce Californios, the Americans diverted off the caretta road along the valley edge, to taking another old road (today identified as “Old San Pasqual Road) into modern day “Kit Carson Park” in Escondido.

The Americans arrived at the Snook Adobe at approximately two in the afternoon. They stayed there for no more than a few hours when they took off again to reach camp at the Rio Bernardo River before sunset. Sunset on this day would be at 4:50 p.m. The American force was moving south between Mule Hill and where the current highway is, Interstate-15, through where today the North County Fair Shopping Mall is located.

There was nothing then but open range, no trees, as they moved in a large square formation. In the middle of the square formation were their wounded laid out on six travois as well as their supplies on pack mules. They had a few head of cattle moving in the front that they had just appropriated from the Indians tending the Snook Adobe, in addition to a few chickens.

When the Americans got approximately a half mile from the Snook Adobe, and half mile yet from the river, the Californios poured out from the ravine from behind the Snook Adobe and started an attack to their rear.

* * *

The rediscovery of the actual location of Mule Hill occurred in approximately 1964. A local amateur historian, Cloyd Sorenson, and his wife, hiking near the base of Mule Hill, began to discover pieces of old brass debris appearing to be military in nature. The location was specifically between the two rock outcroppings facing southwest, at the bottom of a wash formed between both. Until this time, the exact location of Mule Hill was debatable.

By 1966, a large white cross had been erected just south on a nearby mountaintop (Battle Mountain) commemorating the event. It is still there, located just east of the Escondido Freeway (Interstate-15) and just south of Pomerado Road.

However, Sorenson felt that the hill with the large white cross was not in fact where Mule Hill had occurred. He and his wife began to explore another hill due north.

They followed the debris trail upward, towards the top of this new hill. At the top, Sorenson found even more artifact debris, some even visible upon the surface. He reached down and picked up one such item. It was a soldier’s belt buckle cracked in the middle, the crack later attributed (according to Sorenson), to a lance blow.

Sorenson quickly realized what he had stumbled upon and understood the urgency of having a professional archaeological dig performed there and, the location once and for all established. Both he and a friend named Colonel Berkeley R. Lewis, contacted an acquaintance, Konrad Schreier, a historian with the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History. This resulted in the first major archaeological sweep ever conducted of Mule Hill and it retrieved 169 pieces of artifact debris from Kearny’s soldiers, from that fateful event in December of 1846. In addition, it officially and finally established the exact location of Mule Hill. It should be also noted that all the artifacts recovered from Mule Hill by Konrad Schreier in 1970 were turned over to the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History. By 1998, the SLP had established that all these artifacts recovered by Schreier were officially lost by the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History. Their whereabouts have never been known since.

Today, the correct Mule Hill can be located on the Mule Hill Trail. The trail is located just south of Bear Valley Parkway, east of the Escondido Freeway (Interstate-15) at the Via Rancho Parkway exit. The hill can be seen from the road and is just east of the historical, Sikes Adobe and, the PGFA Golfing facility.

By 1994, the SLP had begun to take another fresh look at Mule Hill. The property was owned by the City of San Diego and part of the San Dieguito River Park Project, as well as a registered site under the “American Battlefield Protection Program”. The then–current assessment of the hill was that it had remained largely dormant since the 1970 archaeological sweep by Schreier. Despite Schreier’s recommendation that further archaeological digs be considered at Mule Hill, none were ever conducted. State Rangers through the years continued to report non-authorized digs and pilfering of artifacts by treasure hunters at Mule Hill. This resulted in not only priceless artifacts lost forever from the site, but also the loss of extremely valuable information for future historians. Artifact recovery data helps to assess information from a site and, help reconstruct a more clear and accurate picture of what transpired there.

In the case of Mule Hill, this involved five days with General Kearny and his men in December of 1846.

What also became critically important to the SLP in making new discoveries about Mule Hill, was the hope that the City or County of San Diego, or State entities, might help finance yet another complete formal archaeological dig at Mule Hill. This would not only help save what historical artifacts might still remain there, but also help give new insights into what had occurred during the standoff in 1846.

It was noted that the San Pasqual Battlefield Visitor’s Center, which housed a small museum commemorating the battle, did not have one artifact from either the Battle of San Pasqual or from Mule Hill. The SLP then created the first of its kind computerized database of every artifact known to exist that was reported to be from either the Battle of San Pasqual or, from Mule Hill. Every single artifact reported as being from the Battle of San Pasqual was catalogued, serial numbered, its current location recorded, the location of where it was found, and its subsequent disposition such as to museum or private collection. Items proven to not actually be from the period or battle were also identified.

The new database also culminated scores of interviews with people from local communities to all over the southwestern part of the United States, who claimed to have artifacts obtained from either the battle or from Mule Hill. With Mule Hill, a major break-through occurred when the SLP found several treasure hunters who came forward to not only disclose information about artifacts they had found on Mule Hill, but to show exactly where those artifacts had been located. From this came a flood of new data that had never been known before. While the dig of Konrad Schreier in 1970 uncovered a military baggage burn site, the artifacts uncovered by treasure hunters, and the locations where they were found, gave the SLP a never-before-seen insight into what was occurring on Mule Hill and possibly where.

What the SLP found was that Mule Hill served as a prime example of what happens to a historical site when Federal, State, or private organizations, fail to acquire the resources needed to save such a site through archaeological recovery of artifacts. Saved from eventual loss of not only artifacts pertaining to that event and location, but also historical data recorded from that site that would have helped create an accurate historical picture of events that had transpired there.

* * *

Mule Hill – Treasure Hunters – Discoveries

At this same time, the Site Location Project was becoming aware of a growing problem at both the battlefield and at Mule Hill – Treasure Hunters!

This was a group and class all on its own. While City, County, and State budgets were often difficult to come up with funds for archaeological digs at various sites throughout San Diego, treasure hunters took advantage of this shortfall. Often armed with state-of-the-art metal detectors, they too did their historical research, locating sites and then hunting for artifacts at them. Year after year, the potholes left behind by their digging were always seen both at the fifty-acre State Battlefield Park, as well as at Mule Hill. The State Parks simply did not have enough rangers to always watch over the two sites on a twenty-four/seven day a week basis. As it was already, the San Pasqual Battlefield Park was only opened a few days of the week. At Mule Hill, located five miles west, there was nothing but rural terrain with no park and not even accessible to the public.

Studying the problem from several different angles, the SLP decided that the best way to locate and preserve the battlefield and Mule Hill, was to locate all relevant locations to each site and, then approach the City, County, and State officials with a planned project to have formal archaeological digs conducted there. By conducting archaeological digs at both sites, all relevant artifacts would be located and permanently retrieved for preservation, display, and education.

This way, treasure hunters would have nothing left at these sites to take, plus, the battlefield museum would finally have artifacts from the battle for presentation to the people of the State of California and the rest of the United States. Understanding this, one can appreciate what a complete surprise it was when the Site Location Project received a phone call one day from Battlefield Museum Ranger Joanne Nash.

Joanne reported a gentleman in his fifties had entered the museum reporting that he had artifacts from Mule Hill. She stated that he was a treasure hunter and, maybe the SLP might be able to obtain some authentic artifacts from him for the museum.

A meeting was arranged with the treasure hunter (also referred to as “relic hunters”) and an alias is used for his name to maintain continuum of this story. The gentleman, tall, white hair and glasses introduced himself as Cobb Smith. He lived out of the State and told a remarkable story.

As a young boy, his father often took him treasure hunting up on Mule Hill. Learning metal detecting at an early age, he grew up becoming an expert metal detectist. With his father, they had found over a hundred artifacts from the U.S. Dragoons there in 1846. His father now deceased, Cobb had continued scouring and retrieving artifacts from Mule Hill his entire life. Now living out-of-State, he stated how when he returned to the area on visits to nearby relatives, he would still hunt for artifacts there. Cobb had several hundred authenticated artifacts from Mule Hill. He was an unbelievable find.

Cobb was a professional treasure hunter and told many stories of locating State and Federal sites across several southwestern States. He had amassed a very large private collection back at his home. Treasure hunters like Cobb often held huge private collections of American history. These “private collections” rivaled, and in some cases, surpassed, what major museums had in their collections. To private collectors, their acquiring’s were in demand and worth a lot of money. Thus, treasure hunters stole America’s past and sold it off to private collectors.

In Cobb’s case at Mule Hill, he had over a hundred pieces of artifact debris, maybe even over two hundred from this site, which Californians and other Americans would never get to see. Since the crime of stealing the artifacts from such sites by the State Penal Code was only a misdemeanor, it had to be witnessed by a law enforcement officer in order for he or she to make an arrest. Since no one had seen Cobb actually dig up and take any items from the hill, he could not be arrested for taking the items. At the same time, Cobb could not loan out the items to any California museum because the artifacts had been illegally obtained and State Policy would not allow the display of such obtained type of artifacts.

Why Cobb Smith basically turned himself in to the State Parks Ranger at the Battlefield Museum and, was willing to possibly show the museum artifacts he had from Mule Hill, is unknown. Was he trying to make up for all the artifacts he and his father had pilfered from the hill? Was he now trying to seek absolution from the State Parks for his years of digging on the hill? He even offered to help the Battlefield Museum in any research it may be doing requiring a metal detectist.

From the perspective of the Site Location Project, what was much more tragic by treasure hunters digging up and stealing artifacts, was the hard data lost forever from each and every artifact removed. Just as law enforcement personnel take pain staking measures at crime scenes with each and every single piece of evidence left at the scene, exact information of how and, where each and every artifact is found, helps archaeologists and historians reconstruct the scene played out at that location in history. However, then Cobb surprised everyone.

Cobb had kept a meticulous map of Mule Hill, plotting on it, exactly where he had dug up every artifact across decades. With this information, the Site Location Project met with State Ranger, Joann Nash, to arrange a deal with Cobb Smith. If the State did not pursue Cobb for his stealing of the artifacts from Mule Hill, would he be willing to show us some of the artifacts at the museum? In addition, and more importantly, would he be willing to go with Site Location Project personnel to Mule Hill, and let them record where each and every artifact located was dug up at? To the SLP’s excitement, both the Museum and Cobb agreed to the arrangement.

The result of this arrangement by the SLP was unique and a first for the San Pasqual Battlefield. It resulted in the first of its kind understanding into what was happening on Mule Hill in December of 1846 and where. It would also give some insight into John Cox’s last days there. The data, once assessed, would give the SLP some very speculative understandings of what was going on atop Mule Hill during December of 1846.

After numerous trips to Mule Hill, the SLP pinpointed where each and every artifact had been located and removed from by Cobb Smith. Almost every item was found at three inches down. In addition, over 149 artifacts appropriated by Cobb Smith from Mule Hill were recorded into the SLP database for further research purposes.

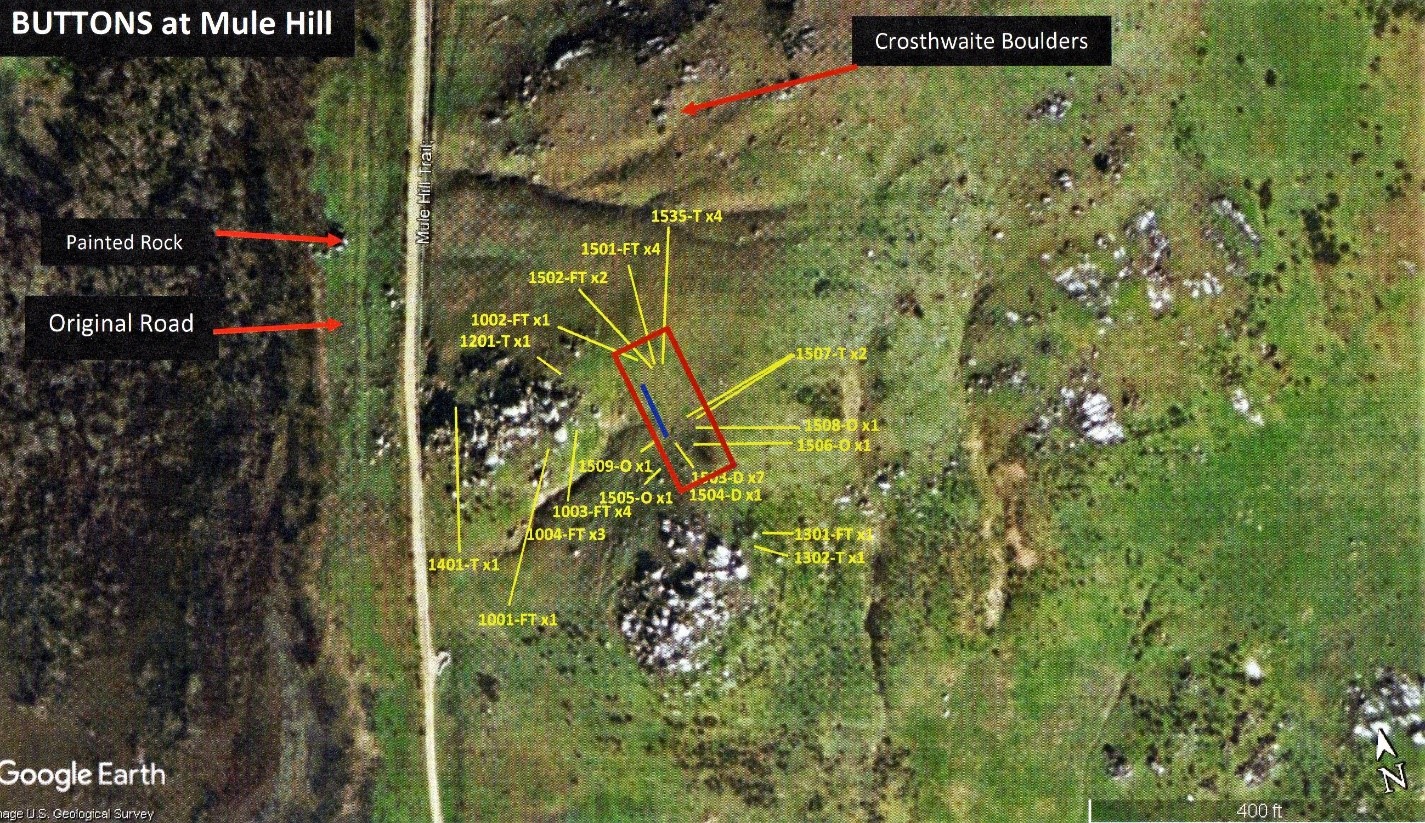

The items were then plotted on an SLP aerial map of Mule Hill and broken down into designated type of artifacts. Following the plotting, study, and assessments made at the Little Bighorn Battlefield in Montana, the SLP then began to analyze the findings upon Mule Hill by Cobb Smith.

Although speculative in nature as all history is, the assessment by the SLP, was based on factual findings of identified artifacts and their exact locations found upon Mule Hill. A particular focus was on military buttons found from uniforms and, artifacts involving weaponry and ammunition.

The SLP established that the Field Hospital was most probably located a top the hill, just inside the State property fence-line, in between the two large rock-croppings facing west and south. This assessment is given based on findings of at least thirty buttons found strewn about this one small location at the top of the hill. All buttons were confirmed as military issue, 1846. The button assortment in this one area alone consisted of 15 dragoon, 6 trousers, and 6 flattops. Two officer’s buttons were also located just east and, one more directly south of this site.

The speculative answer to such a large number of buttons found at one specific location is that this was where uniforms were being torn or cut up for use as bandages for the wounded. The close proximity of officer’s buttons would be consistent with the officers camping close to the wounded soldiers. It must be remembered that numerous officers were wounded, some severely, and all requiring medical treatment too.

To further give credibility to this location as the field hospital where the wounded were laid out, a few years later, the SLP would locate another treasure hunter, who like Cobb Smith, had retrieved an artifact a top Mule Hill. The artifact, examined, photographed, and catalogued by the SLP, was a confirmed standard army issued, flintlock-percussion cap pistol, for all Dragoons. He had also plotted exactly where it had been found. It was found at nearly two feet down in what may have been an original trench or pit. It was located just a few feet from where the field hospital is suspected to have been located at, just directly outside the State property fence-line.

Almost every single artifact that had been found dating to 1846 had been found at three inches. Why was this one found at over two feet down in the earth. Had it been buried purposely and if so, why?

Once again consistent with where the location of the field hospital was located, indeed for sanitary and humane reasons, a toilet, in the form of a trench, would have been located close to the wounded soldiers who could not move or, not move very well due to injuries. One of them was John Cox.

A study of soil composition around the lone artifact suggested a large pit or trench had been originally dug at the site. The SLP’s speculative assessment on this find was that one of the soldiers had purposely hidden the pistol by throwing it into the pit. This, acting on General Kearny’s orders issued on December 9th, 1846, to destroy all excess baggage so that it did not fall into the hands of the Mexicans. Did a soldier toss this pistol into a community toilet, after several days of use figuring no Californios would go looking for it there?

While nothing as congested as at the suspected field-hospital site, other uniform buttons were found strewn about the west faced rock-cropping. Only two buttons were located on the south rock-cropping. This suggested to the SLP that a majority of soldiers were mostly congested on the western rock cropping facing west. This was also consistent as it was farther away from the Californios position located southeast across the valley floor. It also overlooked where they had their animals grazing, had access to water, and where one of their howitzers was positioned on the road.

A lot of other 1846 related artifact debris was found all through the rocks on the western faced rock-cropping which was non-military such as horse tack, nails, and can debris.

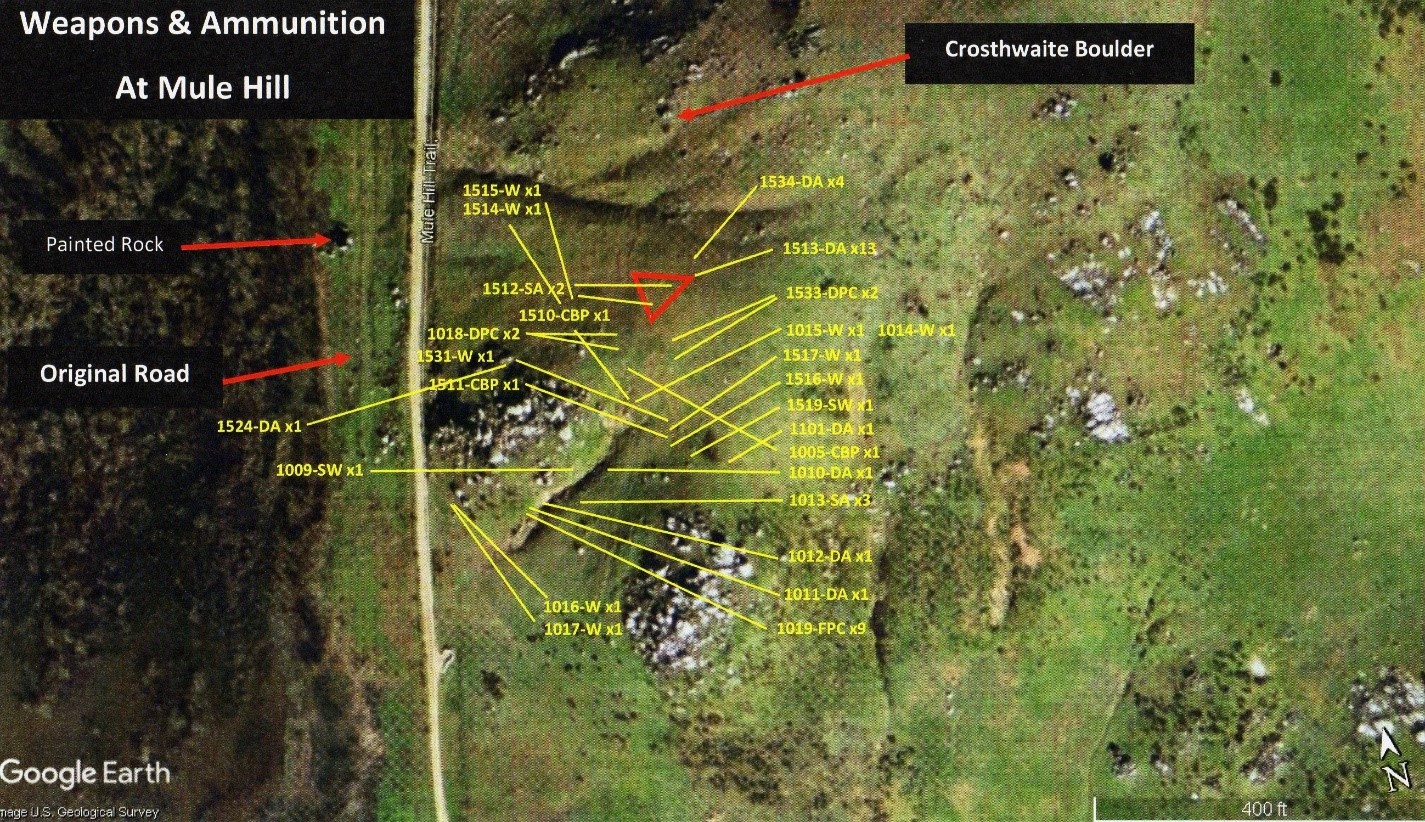

The layout of artifact debris related to weapons and ammunition also painted an interesting picture, especially at two specific locations on Mule Hill.

Cobb had located just northeast of the west-faced rock-cropping, both inside and out of the corner of the State-owned property fence line, 13 perfectly unused, dropped, 44cal. musket balls buried at three inches below the surface. The Dragoons were using 52cal. and 54cal. musket balls. The Californios however were using a variety of different sized musket balls because the few that had weapons, were using their own privately-owned muskets.

In addition, two spent or used 52cal. musket balls were found impacted into the earth right in the middle of the thirteen dropped musket balls.

Ammunition was precious to anyone then, especially in a battle. So, who and how, did someone drop and then leave behind thirteen dropped 44cal. musket balls? Who was shooting at them and why?

There was more. One location showed signs of a possible firefight on the lower southwest portion of the western-faced Rock-cropping.

What exactly happened to John and his fellow Dragoons that faithful December 7th of 1846. They were on their way to San Diego and going to camp that evening along the Rio Bernardo River. What really happened at Mule Hill? How did they end up there and exactly where did it all happen at?

Before the SLP, all that was known about Kearny’s forces on Mule Hill in 1846 was that they were attacked by the Californios and, fought a brief skirmish with them to take possession of the hill. There they sat until December 11th, starving and eating their own mules to stay alive.

As far as the physical hill itself, everyone had originally misinterpreted Emory’s topographical map and had focused completely on the southwest end of the hill. Specifically, between the two rock-croppings. His topographical depiction had instead clearly shown the large enclave on the west side of the hill as it faced west. What was both he, and Phillip Crosthwaite, trying to show everyone?

Caught in a very vulnerable position that offered no cover or concealment from the enemy, the Americans made an instant maneuver to get from the middle of the valley floor to the closest high ground as possible. It was Mule Hill and it was 200 yards away.

Being attacked from its rear towards the Snook Adobe, the American formation now turned completely around to face its enemy. In the melee that now ensued, the soldiers lost their cattle and chickens that had been in the front of their formation. Their priority now was to protect their wounded and supplies in the middle.

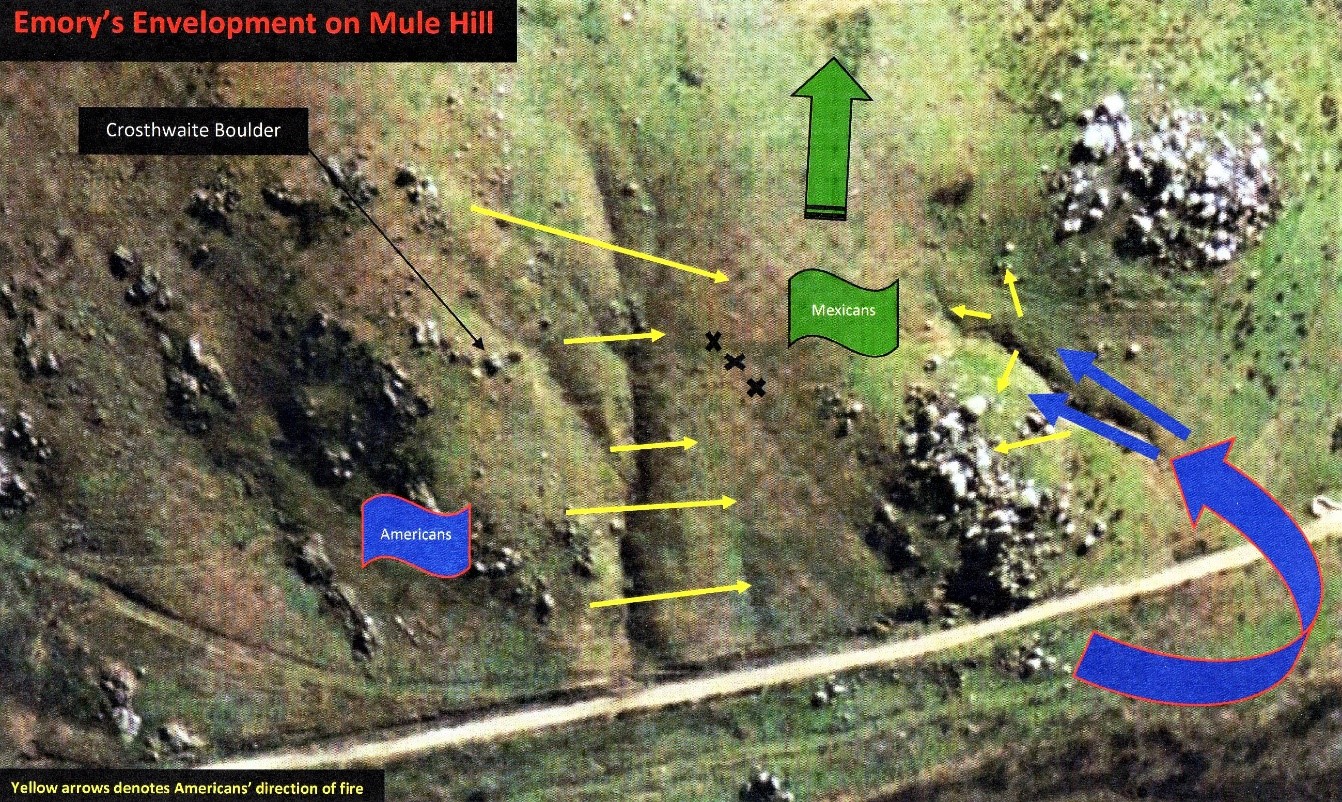

With General Kearny seriously wounded, Captain Turner ordered the force, on Kearny’s orders, to move quickly to the hill. Despite under attack, the Army detachment moved with discipline and order. As shown on Lt. Emory’s topographical map, the U.S. Army got to the northwest corner of Mule Hill through executing three rows or large squads, one behind the other, facing the enemy due south, while they moved their entire force into the large enclave directly facing west and, located between the northwest and southwest points of the hill.

The “Crosthwaite Boulders” seen in the 1897 photograph are located on the left (north) side of this enclave towards the top. As the U.S. Army was moving into this enclave, the Californios had broken off about 30 of its men on horseback, who had now ridden around the eastern top of the hill and, were now enveloping Kearny and his men from above. The Californios began laying down fire on the Americans with some of the Californios firing from their saddles and, others who had dismounted and were firing from behind boulders located on the western rock-cropping.

Some of the first-hand descriptions of this action are given:

“ … just before sunset we were again attacked. The enemy came charging down a valley; about one hundred men well mounted. They were about dividing their force, probably with a view of attacking us in front and rear, when General Kearny ordered his men to take possession of the hill on our left.”

Col. Alexander Doniphan

“Upon arriving at the valley of San Bernardo, a body of the enemy who had secreted themselves, made an attack upon their rear and attempted to prevent the Americans from encamping at a point in the centre of that valley, well protected by rocks.”

Major Swords

“They then charged on us, coming in two bodies, we were compelled to retreat about 200 yards, to a hill of rocks that was to our left.”

Kit Carson

“We arrived in the valley, and as we approached its centre the enemy came dashing forward at the charge, from out of a ravine, more particularly for the purpose of driving off the cattle we had collected. – We halted and faced the rear, and finding that they aimed to get possession of a hill we wished to occupy, we moved by the left flank, and took the hill;”

Capt. Gillespie

This engagement is described by Philip Crosthwaite in an interview by Judge Benjamin Hayes:

“The Californians came sweeping out of the wooded Canada north of the house, over the hill, and down the sides of the house, meeting beyond it for a charge upon the Americans who were then upon the San Diego Road, and about to cross the San Bernardo river.”

Phillip Crosthwaite

As Crosthwaite goes on describing this engagement, he mentions some boulders that the soldiers get to and then use as “breastworks” against the Mexicans. The SLP believes that these in part, are the very boulders that Crosthwaite had his photograph taken next to (identified as site SLP-S- 15), located at the northwest corner of Mule Hill. “This is the second battle-ground: upon a hill in front – ½ mile S.E. of the Snook’s H House: many boulders here and there supplying the place of breastworks …”

Instead of what previous historians had originally thought; that the Americans had rushed to Mule Hill to heroically fight and take the high ground from the Mexicans who had ridden upon it – a new picture was beginning to emerge.

What in fact had happened was that the Americans had left the Snook Adobe site, moving south in a square formation; excluding officers, almost all were on foot and, with wounded and provisions (including cattle) in the middle of the square. They were moving slowly across the valley floor between the present location of Mule Hill and Interstate-15. They were approximately 200 yards from the northwest corner of the base of Mule Hill, moving south. If the Americans arrived at the Snook Adobe site at approximately 2:00 p.m. as stated by Gillespie, and remained there for no more than two hours, then they were moving southward towards Mule Hill either just before or after 4:00 p.m. The sun would set that day at 4:42 p.m.

What we do know for sure is that the Americans, upon venturing out approximately ½ mile from the Snook Adobe and onto the valley floor, they came under attack almost immediately after leaving the adobe. The Mexicans, in a brilliant maneuver, attacked the Americans from their rear. There then is an actual battle engagement by the Mexicans of the Americans on the valley floor. The Americans turned and faced the Californios. Gunfire is exchanged by both sides. All this is happening before the Mexicans are atop Mule Hill and before the Americans even head that direction. This site was identified by the SLP as site SLP-S-10.

Emory’s map shows the Americans facing a head-on attack from their rear as well as a carefully maneuvered three-tiered flanking movement of U.S. Forces onto the closest piece of cover they can get to for protection – the northwest corner of Mule Hill. This is clearly a very defensive maneuver against a head-on attack from their rear. Notice that Emory notates the words “Enemy Repulsed.” Gillespie also notes, “Pico’s column attacking.” The prior belief that the Americans originally charged up Mule Hill to take the high ground from the Mexicans is not accurate. The truth is that the American forces were initially engaged in battle on the valley floor, defending themselves from a full attack by Mexican forces.

While many present–day historians, many of them former Army Officers, deny that the Kearny’s Army ‘retreated’ to Mule Hill, the SLP duly notes that Kit Carson himself notates that they (the Americans) in fact “retreated” towards Mule Hill.

In the dramatic account of the taking of Mule Hill by American forces, Emory took about six to eight men around and between the rocky outcroppings and began to lay down ground fire up towards the Mexicans atop the hill. Some of the men involved were Emory’s men and some belonged to Captain Gillespie. At the same time, the rest of Kearny’s soldiers still at the northwest base of Mule Hill (SLP-S-15) were also laying down ground fire which placed the Mexicans in a deadly crossfire situation. Emory and his men finally took the top of the hill. At least five of the Californios were shot, some very severely, and at least three right out of their saddles. The skirmish was brief, probably lasting no more than between three to five minutes. The Mexicans retreated, leaving behind lances and ammunition but retrieving their wounded.

“We immediately moved by the left flank toward a round hill well protected by rocks, the top of which the enemy gained possession as we reached the base, but were soon dislodged by Captain Emory, at the head of a small party of his own and my men.”

“The rifles had knocked three of the Californians from their saddles, making them leave three lances in their hasty fight.”

Capt. Gillespie

“ Thirty or forty of them got possession of the hill, and it was necessary to drive them from it. This was accomplished by a small party of six or eight, upon whom, the Californians delivered their fire; and strange to say, not one of our men fell. The capture of the hill was then but the work of a moment, and when we reached the crest, the Californians had mounted their horses and were in full flight. We did not lose a man in the skirmish, but they had several badly wounded.”

Lt. Emory

“This the Californians reached first in the race: after some ineffectual firing, they retreated from it and the American camp was forced in an open space among the rocks. On the hill, some of the Californians were wounded: sometimes by galloping up too near.”

Philip Crosthwaite

“ … attacked right at Mule Hill …. Some of them [Mexicans] reached the hill before we did, continued firing but nobody got shot. There appeared some confusion among us – no regularity – confusion among the officers and the topographical officer (Liet. Emory) a noble man … brave, cool, and deliberate.. by sword and said “Men, follow me.” They went ahead and saved the command from them. By his actions, Mule Hill was saved.”

Pvt. William Dunne

“They [Mexicans] were about dividing their force, probably with a view of attacking us in front and rear, when Gen. Kearny ordered his men to take possession of a hill on our left. The enemy seeing the movement, struck for the same point, reaching it before us, and as we ascended, they were pouring a very spirited fire upon us from behind the rocks. They were soon driven from the hill, only one or two being wounded on our side.”

Col. Alexander Doniphan

“ … as they stepped from behind the rocks to make their escape we fired at them and killed and wounded several – they made their escape so rapidly that many of them dropped their arms in their flight.”

Major Henry Smith Turner

The SLP realized that the Americans were initially on the northwest corner of Mule Hill, adjacent the Crosthwaite boulder.

This is where the Americans ran to after coming under fire at site location SLP-S-10 on the valley floor. The SLP also realized that the large ravine separating the location where the Crosthwaite boulder is located, and the two rock-croppings, is the same enclave shown on Emory’s map.

Read carefully Kit Carson’s own words as he describes this:

“They then charged on us, coming in two bodies, we were compelled to retreat about 200 yards, to a hill of rocks that was to our left. After we had gained our position on the hill, the Californians took another hill about 100 yards to our left, and then commenced firing.”

Here is the same quote but with locations penciled in:

“They then charged on us [ from SLP-S-10], coming in two bodies, we were compelled to retreat about 200 yards, to a hill of rocks that was to our left [northwest base of Mule Hill]. After we had gained our position on the hill [SLP-S-15], the Californians took another hill about 100 yards still to our left [southwest rock-cropping], and then commenced firing.”

What is known is that the nearly thirty to forty Californios had dismounted and had taken firing positions among the rocks on the southwest rock-cropping. Therefore, nearly 30-40 horses are being maintained very close to this position and quite possibly, between the rock-cropping and where the three x’s are shown in the above related depiction.

When Lt. Emory and his small group of men begin to envelope the rock-cropping where the Californians are at, the Mexicans quickly find themselves in a cross fire as well as getting surrounded. They then run from the rocks to their horses, mount with no cover or concealment and instantly become targets of the highly trained U.S. dragoons and their muskets. This is where most of the Californios suffer the few causalities that they do.

Codes 1512 & 1513 – From a first-hand eyewitness account, we know that three Mexicans were shot out of their saddles atop Mule Hill. At this location was found a few spent (fired and impacted) musket balls (.54 cal.) in addition to three separate large piles of unused musket balls (.44 cal.).

At first, it was not understood who or, why someone, or individuals, left three separate piles of unused musket balls at this location? Musket balls, especially in war, are a precious resource and not readily left behind in quantity. Here, thirteen unused .44 cal. musket balls (consistent with calibers used by the Californios) were found in three, separate piles at this location. The two spent .54 cal. musket balls (consistent with American Army issued muskets) were also found at this location. The very interesting coincidence is the number “three.” Gillespie describes ‘three’ Californians shot out of their saddle as well as Cobb Smith discovers ‘three’ separate piles of dropped .44 cal. musket balls.

Was this the exact location where 3 Mexicans were shot out of the saddles, fell, and dropped their musket balls from open pouch holders attached to their person?

Code 1019 – Here was found a large amount of fired percussion caps (same type used by U.S. Army circa. 1846), which is consistent with eyewitness accounts of Emory’s men firing on the Mexicans as they advanced up towards the top of the hill. Nine fired percussion caps suggest a sustain rate of fire from this position, most likely from the same weapon. To know how long it would take for a Dragoon to reload and powder his musket after each shot, and to lock in on a target and fire, would give us an approximate amount of time that this shooter was at this position. This location may have been one of their firing positions.

Also found at this location are two dropped musket balls. One is a .30 cal. ball and the other, a .31 cal. (pistol). Emory’s six-to-eight men consisted of a few of his men and a few of Captain Gillespie’s. Since Gillespie’s group were made up also of civilian volunteers, their specific caliber of weapons would have been assorted.

There is very interesting evidence also found up this gully/ravine, moving towards the top of the hill of what appears to both incoming rounds as well as firing positions.

Code 1013 – At least 3 fired and impacted musket balls (caliber unknown) are found here. Was one of Emery’s group being fired upon here by Californios?

Was this gully/ravine being used by some of Emory’s men for cover and concealment as they moved up towards the Mexican’s firing positions at the southwest rock-cropping? Artifact debris recovered here shows activity on both sides of the ravine to the top.

* * *

In order to save a site like Mule Hill from the ongoing scourge of treasure hunters, the SLP saw the urgent need for San Diego and State officials to once and for all, conduct a thorough archaeological dig of the hill. There were simply no resources in place to save the hill from years of ongoing pilfering of the site and the permanent loss of artifacts. The artifacts belonged to the people of the State of California and the United States as a whole. They did not belong to private collectors or in the basement of some out-of-county or, out-of-State museum.

After the discovery of the enormous collection of Cobb Smith, of artifacts retrieved from Mule Hill, along with artifacts recovered by Cloyd Sorenson and Konrad Schreir, as well as numerous treasure hunters, there were many that felt any further digs would prove fruitless. Many archaeologists didn’t want to waste their time on such a project that would result in minimal finds. Further, Mule Hill brought in no significant funding in the way of tax revenues for either the City or the County. There was simply no interest to launch such a project.

The SLP then began to push a new strategy. If a simple field survey was conducted of a small area on Mule Hill, and it were to recover any artifacts pertaining to the battle, then could the SLP use this as evidence to support a formal dig conducted through the backing of the City and County, and supervised by the State? This especially so, since numerous archaeologists, historians, and governmental agencies, had long voiced that there were no more artifacts left at these locations due to flooding, treasure hunters, etc.

In 1995, the SLP received permission from the Battlefield Museum to conduct a small and random field survey a top Mule Hill to answer this question. It utilized Cobb Smith who had volunteered to assist the SLP in its ongoing research. The small area selected was the top of the western-most rock cropping, not far from the suspected site of the field hospital.

Of shock and amazement, no dig was required and yet, perhaps the most amazing artifact ever recovered from Mule Hill was found there by chance.

After conducting several sweeps of the rocky ground area at this location, Cobb wanted to place his metal detector safely down somewhere in order to take a break. Nothing yet had been found. He decided to place his metal detector, still turned on, in between some large boulders. It suddenly went off.

No one was concerned as the top of the hill had for over a century, been a place where locals have often come to hang out and for a variety of activities, including much beer drinking. So, decades of empty beer cans of a sort were strewn everywhere between rocks and usually what was found if one’s metal detector went off.

But this was different. The reading was off the scale for an ordinary can and looking down in between the rocks where the reading was coming from, nothing could be seen. Whatever it was, was very deep down between the crevice of the boulders. Finally, someone with an arm long enough but hand small enough, was able to reach down and pull the object up. It was a perfectly intact spur minus the roweling. It was a beautiful discovery.

The Battlefield Museum was elated, as were members of the San Pasqual Battlefield Volunteer Association, with the find. A State Parks Curator confirmed the spur as U.S. Army Dragoon, 1846, standard issued spur. It gave powerful testament that Mule Hill had retrievable artifacts sill hiding there, waiting to be discovered. It also was a testimony to how State and County authorities had just left the artifacts lie for decades, even ‘above’ the ground, unprotected from the elements and treasure hunters. The SLP was hoping to change that for good.

However, there was a far more reaching significance to the finding of the spur. Of hundreds of artifact debris recovered from Mule Hill, the only other spur ever found and documented, was discovered by the Sorenson-Schreier dig in 1970. That spur and, now the one recovered by the SLP, made two spurs.